Camera Obscura

From Inventions

Name commonly used since the seventeenth century but existing in very similar forms since the fifteenth century, referring to the room where images projected by the sun through a hole can be observed, that is, a dark room; also known as "optical chamber".

Contents |

Historic Period

15th-16th C.

Description

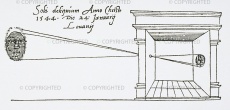

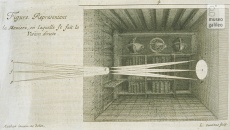

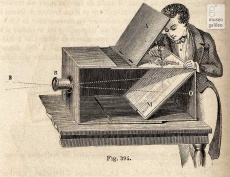

Probably used since antiquity, and certainly since the Middle Ages, to observe eclipses, the camera obscura gradually became an instrument for perspective drawing, which evolved still further with the invention of photography. In its simplest form it consists of a small hole through which light enters a dark room, projecting an image of the scene outside on the opposite wall. One of the first and most enthusiastic descriptions of it is given by Leonardo da Vinci, who astutely compared that luminous phenomenon to the mechanism of vision: “An experiment, showing how objects transmit their images or pictures, intersecting within the eye in the crystalline humour, is seen when by some small round hole penetrate the images of illuminated objects into a very dark chamber. Then, receive these images on a white paper placed within this dark room and rather near to the hole and you will see all the objects on the paper in their proper forms and colours, but much smaller; and they will be upside down by reason of that very intersection. These images being transmitted from a place illuminated by the sun will seem actually painted on this paper which must be extremely thin and looked at from behind…And the same takes place inside the pupil.” (Cod. D dell'Istitute de France, fol. 8r). Some scholars have tried to demonstrate its application to art since the early fifteenth century, citing the first example in those “miracles of painting” mentioned by Leon Battista Alberti in De pictura, described in the anonymous Vita [Life] as paintings contained in a box to be observed through a hole. The first clear reference to the use of the camera obscura in the practice of painting – but without implying that it was actually utilized by painters – appears in Giambattista Della Porta’s Magia Naturalis, published in 1558. Della Porta is also one the first authors to mention the use of a lens to make images clearer, preceded only by Girolamo Cardano in De subtilitate (1550). The lens was mounted in the hole through which the light passed. Della Porta also suggests a method for enlarging and erecting the image using a concave mirror, or an inclined flat mirror, or a combination of convex and concave mirror. By combining these elements – a lens and a mirror – real spectacles could be performed. As in a movie, the spectators saw the persons and animals moving about outside projected onto a screen, in a specially constructed scenario: “Scenes of hunting, banquets, enemy armies, games and all sorts of things… and one inside the camera obscura will see all this so clearly that he will be unable to say whether it is reality or illusion … I have frequently shown such spectacles to my friends, who have been immensely delighted at this amazing trick; and I was unable to change their minds either with natural reasoning or with explanations based on optics, until I revealed the secret to them” (1589, Book XVII). Della Porta also suggested that less expert painters should use this artificial eye: “If you are incapable of portraying a person or any other thing… then this is an art you should learn. When the sun shines through a window, place the persons you wish to portray near the pinhole, with the light falling on them, taking care that the sun’s ray does not fall directly onto the hole. Opposite it, place a sheet of white paper or a panel, and position the persons under the light, moving them backwards or forwards until the light projects a perfect image of them onto the panel. And one who is skilled at painting will affix the colours there where he sees them on the panel, and will depict the expressions of the faces; so that when the image disappears, the painting will remain on the panel, appearing on the surface as if seen in a mirror.” Ten years later, this “natural manner of putting in perspective” was also described by Daniele Barbaro in his Pratica della Perspettiva [The practice of perspective] (1568), in a chapter illustrating mechanical instruments used for perspective drawing, from Albrecht Dürer’s famous “window” to the less well-known distantiometer of the Medicean engineer Baldasarre Lanci. Barbaro does not describe the mirror but, like Della Porta, suggests the use of a lens, specifying its form: “Take a pair of eyeglasses for the elderly” he writes, “those are thick in the middle and not concave, like spectacles for young people, who are short-sighted”. The proper lens for a camera obscura should thus be of the positive, converging type, plano-convex or double-convex, like those used to correct farsightedness. A negative lens, of the diverging type, plano-concave or double-concave, of the kind used to correct myopia, would have produced no results at all.

Bibliographical Resources

Fubini R. e Gallorini, A.M., L’autobiografia di Leon Battista Alberti. Studio e edizione, in “Rinascimento”, XII, 1972, pp. 21-78.

Pastore, Nicholas e Rosen, Edward, Alberti and the Camera Oscura, in “Physis”, XXV, 1984, pp. 259-269.

Barbaro, Daniele.La pratica della perspettiva di monsignor Daniel Barbaro ...: opera molto utile a pittori, a scultori et ad architetti: con due tavole, una de' capitoli principali, l'altra delle cose più notabili contenute nella presente opera. In Venetia, appresso Camillo & Rutilio Borgominieri fratelli, 1569, IX, V.

Della Porta, Giovanni Battista, Magia Naturalis, sive de miraculis rerum naturalium, libri IV, Napoli, 1558; edizione ampliata in 20 volumi, Napoli, 1589, lib. XVII.

Lindberg, David C., The Theory of Pinhole Images from Antiquity to the Thirteenth Century, in “Archive for History of exact Sciences”, 5, 1968, pp. 154-176.

Goldstein, Bernard R., The Physical Astronomy of Levi Ben Gerson, in “Perspectives on Science”, 5, 1997, pp. 1-30.

Existing Instruments

- Musée des arts et métiers, Paris

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 01806-0000-

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 16865-0001-

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 04228-0000-

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 01805-0000-

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 01809-0000-

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 01802-0000-

Paris, Musée des arts et metiers, inv. 01801-0000-

- Museum of the History of Science, Oxford

Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, inv. 92218

Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, inv. 75945

- Departement of history of science, Harvard Univesrity

Departement of history of science, Harvard Univesrity, inv. 0010

Links (External)

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CDUQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.arrigoamadori.com%2Flezioni%2FDidatticaDellaFisica%2FCAMERA_OSCURAB.ppt&ei=SsZjTO65O5TR4ga0k-jkCQ&usg=AFQjCNHBSo50soGYRjIqYyr4wLjfqTV_7g (Italian)

http://www.fotochepassione.com/Storia/meravigliosa-storia1.htm (Italian)

http://www.moebiusonline.eu/fuorionda/Caravaggio.shtml (Italian)

http://brightbytes.com/cosite/what.html (English)

http://www.giantcamera.com/ (A site in English about the giant camera obscura of San Francisco)

http://www.acmi.net.au/AIC/CAMERA_OBSCURA.html (English)

http://www.rleggat.com/photohistory/history/cameraob.htm (English)

http://www.cs-photo.com/obscura/about.php (English)

http://www.cameramuseum.ch/upload/press/Dossier%20de%20presse_4.pdf (French)

Images

Author of the entry: Filippo Camerota