Geometric and Military Compasses

From Inventions

m (1 revision) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Template invention | {{Template invention | ||

| - | |nome= | + | |nome= |

| + | Name coined by the inventor. | ||

|inventore= Galileo Galilei | |inventore= Galileo Galilei | ||

| Line 7: | Line 8: | ||

|data= 1597 | |data= 1597 | ||

| - | |descrizione= | + | |descrizione= |

| + | Invented by Galileo in 1597 but published only in 1606, the "geometric and military compass" served to carry out all of the operations required by the art of warfare: measuring calibers and weights of shot, aiming cannons, solving arithmetical and proportional problems as well as those of plane and solid geometry, calculating gradients, distances, heights and depths. For this purpose its legs bear various scales or proportional lines, called of the "metals", "stereometric", "geometric", "arithmetical" (on the front), "polygraphic", "tetragonic" and "additional" (on the rear). When the compass operates as [[Gunner's Square | gunner's square]], as [[quadrant]] or as [[Geometrical Square | geometrical square]], its legs are held fixed at right angles by means of a "quarter circle" engraved with various scales: the gunner's scale, divided into 12 parts, the degree scale (90°), the gradient scale, divided into 10 parts, and the shadow square scale, divided into 200 parts (100+100). Galileo does not mention land surveying, which however is added to the operations of the "compass" in a version of his treatise published in 1663 at Lyon in the ''Opera omnia'' of Girolamo Cardano. Although the instrument was designed mainly for military purposes, its operations were applicable to any other profession requiring even a basic knowledge of arithmetic and geometry. For example, merchants, bankers, craftsmen, engineers, topographers and astronomers all found it highly useful. Between 1598 and 1608, Galileo instructed some of Europe's most powerful rulers in the operation of his instrument, among them Prince John Frederich of Alsace, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, the Landgrave Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo I Gonzaga. In 1606 he built a silver model of the compass for Prince Cosimo de'Medici, to whom he dedicated the treatise on ''Le operazioni del compasso geometrico et militare'' [The operations of the geometric and military compass] published in Padua that same year. The success of the geometric and military compass, which also brought Galileo some financial gain, provoked a bitter quarrel in the academic world over the authorship of the invention. Already by 1603 Galileo had been alerted to possible plagiarism, when the Dutchman Jan Eutel Zieckmesser presented a compass entirely similar to his own in Padua. Having established the priority of his invention in a public confrontation in the home of Jacopo Cornaro, Galileo decided to write the ''Le operazioni del compasso geometrico e militare'' to forestall claims from any other usurper. Eight months after its publication, however, Baldassarre Capra, who had learned to use the instrument from Galileo himself in Cornaro's home, claimed to have invented the compass and published a text in Latin on its operations: ''Usus et fabrica circini cuiusdam proportionis'', Padua 1607. | ||

|componenti= | |componenti= | ||

Revision as of 11:27, 13 November 2009

Name coined by the inventor.

Contents |

Inventor

Galileo Galilei

Historic Period

1597

Description

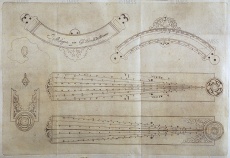

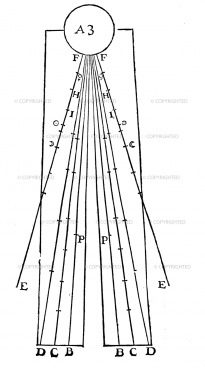

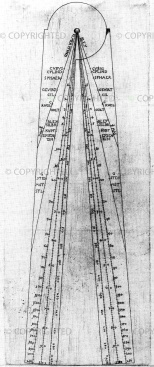

Invented by Galileo in 1597 but published only in 1606, the "geometric and military compass" served to carry out all of the operations required by the art of warfare: measuring calibers and weights of shot, aiming cannons, solving arithmetical and proportional problems as well as those of plane and solid geometry, calculating gradients, distances, heights and depths. For this purpose its legs bear various scales or proportional lines, called of the "metals", "stereometric", "geometric", "arithmetical" (on the front), "polygraphic", "tetragonic" and "additional" (on the rear). When the compass operates as gunner's square, as quadrant or as geometrical square, its legs are held fixed at right angles by means of a "quarter circle" engraved with various scales: the gunner's scale, divided into 12 parts, the degree scale (90°), the gradient scale, divided into 10 parts, and the shadow square scale, divided into 200 parts (100+100). Galileo does not mention land surveying, which however is added to the operations of the "compass" in a version of his treatise published in 1663 at Lyon in the Opera omnia of Girolamo Cardano. Although the instrument was designed mainly for military purposes, its operations were applicable to any other profession requiring even a basic knowledge of arithmetic and geometry. For example, merchants, bankers, craftsmen, engineers, topographers and astronomers all found it highly useful. Between 1598 and 1608, Galileo instructed some of Europe's most powerful rulers in the operation of his instrument, among them Prince John Frederich of Alsace, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, the Landgrave Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Mantua, Vincenzo I Gonzaga. In 1606 he built a silver model of the compass for Prince Cosimo de'Medici, to whom he dedicated the treatise on Le operazioni del compasso geometrico et militare [The operations of the geometric and military compass] published in Padua that same year. The success of the geometric and military compass, which also brought Galileo some financial gain, provoked a bitter quarrel in the academic world over the authorship of the invention. Already by 1603 Galileo had been alerted to possible plagiarism, when the Dutchman Jan Eutel Zieckmesser presented a compass entirely similar to his own in Padua. Having established the priority of his invention in a public confrontation in the home of Jacopo Cornaro, Galileo decided to write the Le operazioni del compasso geometrico e militare to forestall claims from any other usurper. Eight months after its publication, however, Baldassarre Capra, who had learned to use the instrument from Galileo himself in Cornaro's home, claimed to have invented the compass and published a text in Latin on its operations: Usus et fabrica circini cuiusdam proportionis, Padua 1607.

Bibliographical Resources

Camerota, Filippo. Il compasso di Galileo / Galileo’s Compass, Firenze, Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, 2004.

Camerota, Filippo. Galileo Galilei. Le Operazioni del Compasso geometrico e Militare, commentray by Filippo Camerota, CD-ROM, Octavo, Oakland, CA, 2004.

Cardano, Girolamo. "Hieronymi Cardani Opera omnia in decem tomos digesta". Lugduni, sumptibus Ioannis Antonii Hvgvetan & Marci Antonii Ravavd, 1663.

Drake, Stillman. Tartaglia's Squadra and Galileo's Compasso, “Annali dell'Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza di Firenze”, II, 1977, pp. 35-54.

Galileo Galilei, Operations of the geometric and military compass (1606). A cura di Stillman Drake. Washington 1978.

Galilei, Galileo. "Le operazioni del compasso geometrico et militare". In Padova, in casa dell'autore, per Pietro Marinelli, 1606.

Hambly, Maya. Drawing Instruments 1580-1980, Londra, Sotheby’s Publications, 1988, pp. 135-142.

Museo di Storia della Scienza. Catalogo. A cura di Mara Miniati. Firenze 1991, p. 60.

Righini Bonelli, Maria Luisa; Settle, Thomas. The antique instruments of the Museum of history of science in Florence, Firenze 1978, pp. 18-19.

Turner, Anthony. Early Scientific Instruments. Europe 1400-1800, Sotheby’s Publications, Londra 1987, pp. 157-160.

Vergara Caffarelli, Roberto. Il compasso geometrico e militare di Galileo Galilei. Testi, annotazioni e disputa negli scritti di G. Galilei, M. Berreger e B. Capra, Pisa, Edizioni ETS, 1992.

Existing Instruments

Florence, Museo Galileo. Institute and Museum of the History of Science, Inv. 2430.

Images

Author of the entry: Filippo Camerota