Perspectograph by Ludovico Cigoli

From Inventions

(Created page with '{{Template invention |nome= Has no specific name. |inventore= Ludovico Cigoli (1559-1613) |data= ca. 1610 |descrizione= This instrument is the most important result of Cigol…') |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

|data= ca. 1610 | |data= ca. 1610 | ||

| - | |descrizione= This instrument is the most important result of Cigoli’s studies on perspective. It was invented to allow painters to draw distant objects with the same objectivity as that imposed by the geometric rules for drawing nearby ones. This purpose is emblematically announced already on the title page of ''Prospettiva pratica'' [Practical perspective] where the instrument is illustrated in the form of an impresa bearing the Greek motto “ει παντα σπουδάξεις έφοράν” (“If you strive to observe all things”). Although similar in structure to [[Vignola’s perspectograph]], [[Egnazio Danti’s square]] and [[Buontalenti’s square]], on the operational level the instrument is an entirely original invention. By means of two strings, all of the points observed can be easily transcribed onto a sheet of drawing paper. On one of these strings, a square slides on parallel guides to intersect the visual ray with the vertical section rod. The other string moves a small ball along the section rod until it overlaps the point observed, and this position is automatically traced on the sheet of paper by means of a “marker” tied to the end of the string. The instrument served to draw from life objects, figures, urban vedutas and landscapes, but could also be used to enlarge a drawing on a wall or even on a vaulted ceiling. For the latter procedure, Cigoli devised the solution of inclining the section rod so as to control the drawing of the verticals on the ceiling’s curved surface. This technical stratagem suggested to the artist how to use the instrument for drawing anamorphoses. Portraying an object with the section inclined provides a deformed image that assumes its correct proportions only when observed from a precise viewing point. Based of this experience, Cigoli gives the rule for deforming an orthogonal grid, correcting the empirical construction previously furnished by Vignola. Using the instrument for anamorphoses was proposed again by J.F. Niceron in the second edition of his treatise on perspective. | + | |descrizione= This instrument is the most important result of Cigoli’s studies on perspective. It was invented to allow painters to draw distant objects with the same objectivity as that imposed by the geometric rules for drawing nearby ones. This purpose is emblematically announced already on the title page of ''Prospettiva pratica'' [Practical perspective] where the instrument is illustrated in the form of an impresa bearing the Greek motto “ει παντα σπουδάξεις έφοράν” (“If you strive to observe all things”). Although similar in structure to [[Perspectograph by Jacopo Barozzi Da Vignola |Vignola’s perspectograph]], [[Square by Egnazio Danti |Egnazio Danti’s square]] and [[Square by Bernardo Buontalenti |Buontalenti’s square]], on the operational level the instrument is an entirely original invention. By means of two strings, all of the points observed can be easily transcribed onto a sheet of drawing paper. On one of these strings, a square slides on parallel guides to intersect the visual ray with the vertical section rod. The other string moves a small ball along the section rod until it overlaps the point observed, and this position is automatically traced on the sheet of paper by means of a “marker” tied to the end of the string. The instrument served to draw from life objects, figures, urban vedutas and landscapes, but could also be used to enlarge a drawing on a wall or even on a vaulted ceiling. For the latter procedure, Cigoli devised the solution of inclining the section rod so as to control the drawing of the verticals on the ceiling’s curved surface. This technical stratagem suggested to the artist how to use the instrument for drawing anamorphoses. Portraying an object with the section inclined provides a deformed image that assumes its correct proportions only when observed from a precise viewing point. Based of this experience, Cigoli gives the rule for deforming an orthogonal grid, correcting the empirical construction previously furnished by Vignola. Using the instrument for anamorphoses was proposed again by J.F. Niceron in the second edition of his treatise on perspective. |

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

|immagini= <gallery widths=230 heights=368 perrow=3> | |immagini= <gallery widths=230 heights=368 perrow=3> | ||

| - | |||

Image: 0820_3303_0569-002.jpg | Modello del prospettografo del Cigoli ricostruito in base ai disegni del trattato di ''Prospettiva pratica'', Firenze, Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza.<br /> | Image: 0820_3303_0569-002.jpg | Modello del prospettografo del Cigoli ricostruito in base ai disegni del trattato di ''Prospettiva pratica'', Firenze, Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza.<br /> | ||

| Line 41: | Line 40: | ||

|categoria_1= | |categoria_1= | ||

| - | |categoria_2= | + | |categoria_2= Drawing instruments |

|categoria_3= | |categoria_3= | ||

|categoria_4= | |categoria_4= | ||

Current revision as of 12:01, 27 July 2010

Has no specific name.

Contents |

Inventor

Ludovico Cigoli (1559-1613)

Historic Period

ca. 1610

Description

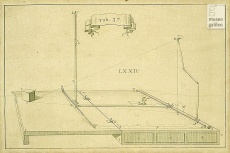

This instrument is the most important result of Cigoli’s studies on perspective. It was invented to allow painters to draw distant objects with the same objectivity as that imposed by the geometric rules for drawing nearby ones. This purpose is emblematically announced already on the title page of Prospettiva pratica [Practical perspective] where the instrument is illustrated in the form of an impresa bearing the Greek motto “ει παντα σπουδάξεις έφοράν” (“If you strive to observe all things”). Although similar in structure to Vignola’s perspectograph, Egnazio Danti’s square and Buontalenti’s square, on the operational level the instrument is an entirely original invention. By means of two strings, all of the points observed can be easily transcribed onto a sheet of drawing paper. On one of these strings, a square slides on parallel guides to intersect the visual ray with the vertical section rod. The other string moves a small ball along the section rod until it overlaps the point observed, and this position is automatically traced on the sheet of paper by means of a “marker” tied to the end of the string. The instrument served to draw from life objects, figures, urban vedutas and landscapes, but could also be used to enlarge a drawing on a wall or even on a vaulted ceiling. For the latter procedure, Cigoli devised the solution of inclining the section rod so as to control the drawing of the verticals on the ceiling’s curved surface. This technical stratagem suggested to the artist how to use the instrument for drawing anamorphoses. Portraying an object with the section inclined provides a deformed image that assumes its correct proportions only when observed from a precise viewing point. Based of this experience, Cigoli gives the rule for deforming an orthogonal grid, correcting the empirical construction previously furnished by Vignola. Using the instrument for anamorphoses was proposed again by J.F. Niceron in the second edition of his treatise on perspective.

Bibliographical Resources

Cardi, Ludovico detto Il Cigoli. Prospettiva pratica di fra Lodovico Cardi ... dimostrata con tre regole e la descrizione di dua strumenti da tirare in prospet. e modo di adoperarli et i cinque ordini di architet. con le loro misure. Firenze, Gabinetto dei disegni e delle stampe degli Uffizi, ms. 2660 A.

Niceron, Jean François. Thaumaturgus opticus, seu Admiranda optics per radium directum, catoptrices per radium reflectum, Parigi 1646, II, pp. 191-204.

Camerota, Filippo. L'architettura curiosa: anamorfosi e meccanismi prospettici per la ricerca dello spazio obliquo, in Architettura e prospettiva tra inediti e rari, a cura di Alessandro Gambuti, Alinea, Firenze 1987, pp. 79-111.

Kemp, Martin. The Science of Art. Optical themes in western art from Brunelleschi to Seurat, Yale University Press, New Haven e Londra 1990; trad. it., La scienza dell’arte. Prospettiva e percezione visiva da Brunelleschi a Seurat, Giunti, Firenze 1994., p. 198-200.

Kemp, Martin. Lodovico Cigoli on the Origins and Ragione of Painting, in "Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz", XXV, 1991, 1, pp. 133-152.

Friess, Peter. Kunst und Maschine. 500 Jahre Maschinenlinien in Bild und Skulptur, Deutscher Kunstverlag, München 1993., pp. 111-117.

Images

Author of the entry: Filippo Camerota